Last month’s History Month concluded with a conference on colonial period cemeteries which was held at the Nagcarlán Underground Cemetery. It is unfortunate that it was the only history conference that I was able to attend, but I think that it was still worth it since I was with two like-minded individuals who were highly knowledgeable with Catholic art.

Since I had been to the place numerous times, I was thinking of wowing both Maurice Joseph Almadrones and Rafael Vicho with whatever interesting stuff that I know of the place. But it was the other way around: they astounded me with their vast knowledge of sacred art, architecture, and music that I didn’t even know existed in the said heritage site. Sometimes, history is not just about dates, events, and personalities. It can also be about art and song.

Please welcome this blog’s first guest blogger, my friend Maurice, as he explains to us his survey of the place. Mao’s observations are perhaps the most detailed descriptions one would encounter on the Internet regarding this unique cemetery. Frequent visitors —including the NHCP itself— might be in for a delightful surprise.

All photos on this blogpost also belong to Mao, except for the last one at the bottom which was taken by Rafael.

Without further ado…

* E * L * F * I *L * I * P * I * N * I * S * M * O *

Nagcarlán Underground Cemetery: A Burial Ground Filled With Sacred Art and Song

Maurice Joseph Almadrones

Last August 31, a rainy Saturday, was my first time to explore Nagcarlán. Despite my bouts of sickness, I really needed to give myself some time to relax. While touring the mountain town, my knee was hurting like there’s no tomorrow. But I had no choice but to walk, right?

When I was a boy, we always passed by the underground cemetery whenever we were to go to Liliw, but I never really gave much thought to see it. So I took the chance to explore it when I attended a lecture there by Asst. Prof. Michelle S. Eusebio on “Colonial Period Cemeteries as Filipino Heritage”. Since the conference was part of History Month, it was hosted by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP).

Here are my observations on the Nagcarlán Underground Cemetery:

1. Besides it being a picturesque place (I’m looking at you, plain tourists), and of course a historical witness to the schemes of the rebellion against Spain, there is much artistic, religious, and socio-cultural value to the place.

a. The cemetery is made from bricks that were most likely produced outside the southern Tagálog region. This testifies to the wealth of the parochial community of the area. Notice that places to the northwest of Banajao have more brick structures compared to the southeast starting from Majayjay to Lucbán and down to Lucena which has more adobe.

b. The cemetery is octagonal (ochavado) in shape. Now, before anyone starts commenting that the octagon “is a testament to our multiculturalism citing Chinese influence” which is also a factor, it is also a Christian symbol of perfection, alluding to the creation and resurrection or “Octava Dies” or “octave” which is actually the full circle of a feast or of creation and life itself. The ancients constructed their baptismal fonts and baptistries in this shape.

c. The mortuary chapel, being preserved compared to many other examples in the region, has an ample seating capacity. Its walls are adorned with azulejos (blue-colored tiles) and baldosas (floor tiles) which were usually imported. Same tiles are seen finishing off the mensa (table) of the stone altar attached to the retablo designed for when Mass was still offered facing God with the people (sorry, Pampanga liturgists). The very same tiles are seen in the nearby parish church.

d. The walls have wooden trims, moldings, and cornices, sometimes mixed in with the masonry trimmings. The ceiling is of a hardwood arched frame with painted panels.

e. The ceiling and the walls were painted in bright colors of orange, gray, cobalt/Prussian blue, yellow, green, and purple, perhaps to contrast the trend of parish churches sporting trompe-l’œil in monochromatic tones. Or maybe to add some color to contrast with the somberness of the rites of the Requiem Masses and Absolutions done in the chapel. The same trompe-l’œil palette is employed to create a faux vaulting in the crypt, also brandished in azulejos.

f. The painted trompe-l’œil false windows inside the chapel have fragments of verses from the Office of the Dead (technically Divine Office / Liturgy of the Hours) for the commemoration of the faithful departed. The fragments are of “Domine, quando veneris judicare terram, ubi me abscondam a vultu irae tuae? Quia peccavi nimis in vita mea” (O Lord, when thou comest to judge the world, where shall I hide myself from the face of thy wrath? For I have sinned exceedingly in my life).

The opposite wall must have contained the next part which reads: “Commissa mea pavesco Et ante te erubesco, Dum veneris judicare, noli me condemnare, Quia peccavi nimis in vita mea” (I dread my sins, I blush before thee: When thou comest to judge, do not condemn me, For I have sinned exceedingly in my life). These were taken by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina himself for a composition.

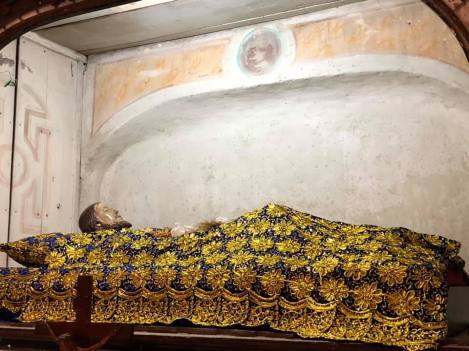

g. The retablo quaintly frames a niche made from masonry and painted simply which contains space for the Santo Entierro (Holy Burial) which is still there. The crucifix on top looks as if it is not the original one intended for the retablo. It seems like the retablo also has a missing top to it; perhaps it may have been overestimated so the top was never realized since it was too tall for the ceiling.

The wooden gradas (gradines) or steps on the altar are devoid of any flourish compared to the retablo sporting Corinthian columns. The retablo itself is reminiscent of the neoclassical style in vogue during the 19th century. The floral detail is crowned by a palm (symbol of victory) and roses / passion flowers (symbol of love / the Passion of Our Lord) intertwined. The gradas have lost the original metal candeleros (candlestick holders).

h. The altar of the chapel, as mentioned earlier, is finished off by azulejos on the mensa. It is still perfect for traditional Latin Mass to be offered. However, as inquired from the curators, the chapel has nearly zero chance of being granted such Mass, thus weaning it from its original function as a place of prayer, which is sad for most heritage places outside churches. They just become display pieces.

2. Going down the portal to the right of the chapel is the stairwell to the crypt. The wall above the stairway’s second landing has fragments of a poem. Sadly, it has deteriorated like much of the artwork found throughout the chapel due to natural humidity, rainwater seepage, vandalism, and of course, human body heat and flash photography, exactly the same problems that the Catacombs in Rome is experiencing. Historian Pepe Alas has tediously researched the poem which reads:

Ve espíritu mortal,

lleno de vida

hoy visitaste felizmente este refugio.

Pero después que tu te vayas,

Recuerda que aquí tienes un lugar

de descanso preparado para tí.

(Translation:

Go forth, Mortal man, full of life

Today you visit happily this shelter,

But after you have gone out,

Remember, you have a resting place here,

Prepared for you.)

No trace of the author exists, but we can only theorize that perhaps a local poet or the parish curate himself may have composed it. It is a very consoling thing to read as one accompanies the dead to be buried in a place of eternal peace.

3. The crypt chapel features:

a. A stone retablo and altar which has a mensa finished off in brown baldosa and has a niche for an image, or perhaps a tall crucifix. Gradines are absent, hinting perhaps that the candeleros, a pair usually rested on the mensa itself. Evidently, someone bore a hole on the body of the altar, perhaps in search of some “treasure” inside, out of curiosity, or because of the testimonies of locals that a tunnel underneath exists which connects the chapel to the parish church of San Bartolomé which is about a kilometer away.

b. Some prominent Nagcarleños are still buried inside including two priests nearest the altar who died in the early part of the 20th century. The others have markers or lápidas that feature art nouveau and neoclassical designs of the early 20th century. The best lápidas in the embossed style of carving seem to come from the talleres (studios) of Manila.

We have not found any marker from the 19th century. Maybe it’s because up until recently the niches were reusable, or maybe the Katipunan rebellion and the American Occupation as well as grave robbers swept away all vestiges of older markers, including the dead.

c. The walls and the vaulted ceiling are painted in the same palette as the chapel above. Although the plaster and paint are deteriorating slowly. We were able to take a couple of photos before an NHCP caretaker approached us informing us that photography was no longer allowed in the crypt — either for the art’s safety OR perhaps our own. 👻

d. The elevated floor of the crypt altar and the stairs were decked in azulejos.

e. To the right facing the altar is a 3×4 meter space, like another side chapel but with no graves and no evidence of a liturgical function. However, the floor contains a 1×1 meter bare area devoid of azulejos. We suspect that it might be a blocked entrance to an ossuary for the disinterred dead (taken out of their plot or niche after dues were not renewed, or to free space for new bodies), or another structure or chapel might be underneath, or perhaps it is an entrance to the rumored tunnel.

f. To the left of the altar is a seemingly blocked up arched doorway hinted by the color difference of the plaster or palitada, and in older photographs, mildew take the shape of the arch. This might be an entrance to another chapel or perhaps the rumored tunnel leading to the parish church. Mr. Alas related that he got the testimony of one of the parish church’s caretakers who allegedly found a way to the tunnel starting from behind the altar but did not pursue finishing the length because it was too dark.

g. The stairwell is lighted and ventilated by one big window, the crypt by two small ones (the putrefying dead needed air too to help speed up decay).

4. The circumferential wall of the cemetery is unique for being a mostly decorative wall with grilled windows compared to other colonial cemeteries where walls double as niches. The windows allow fresh mountain air from Banajao to pass through to the grounds. The wall has detail on top all around akin to stone lacework or the parapets/roof detailing of Buddhist pagodas. There’s your oriental connection.

The outside niches and the chapel were featured in the 1976 film “Ganito Kami Noon, Paano Kayo Ngayon?” where the opening scene shows the burial of Nicolás ‘Kulas’ Ocampo’s (played by Christopher De León) mother complete with funeral procession flowing out of the chapel, and the parish priest in black stole, cope, and a biretta for the internment at a niche to the left of the chapel (Kulas’ mother must have saved much to afford a niche!).

Thank you Professor Nick Deocampo for putting this film to our pedagogic canon.

5. The gate echoes the chapel’s fachada (façade) sans the espadaña (bell wall).

6. The chapel’s façade is in the baroque style with two levels. The second level has scroll designs and, of course, the espadaña designed to support a bell usually tolled when a burial procession enters. It also has two ocular windows; probably for ventilation purposes back in the day. The gate and the chapel have exterior niches however the statuary is missing.

All in all, this mortuary chapel is of adobe and brick much like the nearby parish church.

7. Of course, upon entering, we were greeted by a lush lawn with hedges, but perhaps underneath are the remains of people too since even the grounds were meant for the burial of people. Back in the day, the center of the field might have possessed an atrial cross (a requirement in the building of cemeteries and in the ritual of blessing the grounds for burial).

After the conference. Left to right: Rafael Vicho, Pepe Alas, Maurice Almadrones (author of this blogpost/article), and Dr. Michelle S. Eusebio (event lecturer).

I wonder if those altars still have altar stones

LikeLike

There is no evidence that the altars had altar stones inserted in them because of the absence of slots. Perhaps there were removable ones put in when Mass was offered and taken out after.

LikeLike